New mBio Data Portal Brings Transparency to Genetically Modified Crops in Africa

Genetically modified (GM) versions of crops such as maize, soybean, and cotton have been proposed as a solution to food insecurity and poverty in Africa. In the last decade, private, philanthropic, and government organizations have spent hundreds of millions of dollars launching hundreds of GM agriculture projects on the continent. But many of the details surrounding these initiatives remain opaque to the populations they profess to help.

A new interactive data portal created by researchers and data scientists from the University of Chicago, University of San Francisco, and University of Cambridge brings this information into the light. The mBio (Mapping Biotechnologies in Africa) Project, a collaboration between Brian Dowd-Uribe, Joeva Rock, and the University of Chicago Data Science Institute, unveils the portal today with data on the funding, location, and research status for more than 230 GMO crop varieties in Africa.

The project, funded by the 11th Hour Project, scraped publicly-available financial information, scientific materials, and media reports to create an independent resource for stakeholders both within and outside of Africa, including government officials, nongovernmental organizations, journalists, and international institutions. The resulting database, the largest of its kind, reflects a powerful collaboration between social scientists and data scientists, combining the strengths and methods of each field.

“The impact of biotechnology in Africa is a serious and challenging problem that combines social anthropology, sociology, political science, economics, biology, and many other fields,” said David Uminsky, executive director of the Data Science Institute. “And it was a challenging and hard problem from a data science perspective, to find disparate sources and try to correctly glue all these datasets together in order to understand the who/what/how investigatory work. It’s a core problem, and it is one that’s deeply aligned with the mission of DSI, but we just wouldn’t have been aware of it and the questions to ask of the data without this partnership.”

The portal, built by Launa Greer, Daniel Grzenda, and Trevor Spreadbury of the DSI, includes a searchable financial database of more than 4,000 transactions possibly related to biotechnology from organizations around the globe including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the US Agency for International Development, and the African Agricultural Technology Foundation. With the data, users can track the flows of money between funders, projects, and contractors such as American agriculture giant Monsanto.

The portal, built by Launa Greer, Daniel Grzenda, and Trevor Spreadbury of the DSI, includes a searchable financial database of more than 4,000 transactions possibly related to biotechnology from organizations around the globe including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the US Agency for International Development, and the African Agricultural Technology Foundation. With the data, users can track the flows of money between funders, projects, and contractors such as American agriculture giant Monsanto.

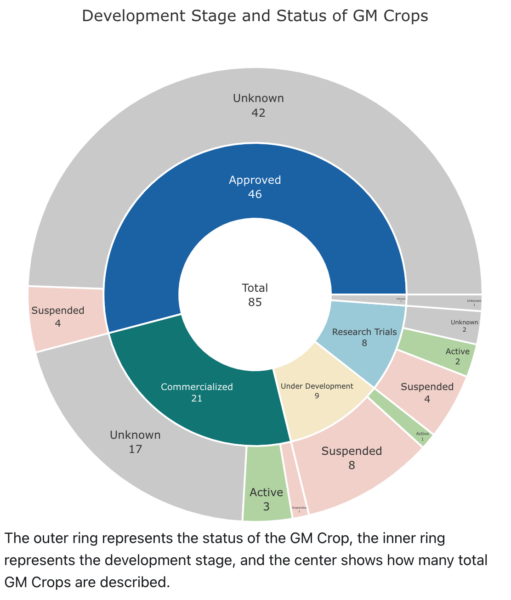

Another database tracks the location and status of dozens of GM research projects, combining data from the International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications (ISAAA) GM Approval Database with reviews of the scientific literature, organizational reports, and media. Users can discover whether projects are active or suspended, whether they are currently under research in the laboratory or field trials, and whether they have led to approved or commercialized products. An interactive map also allows users to click different countries and view a report on all of the documented GM crop projects and developers in that location.

“We said, let’s use our expertise and our tools to dig up all that information, and then provide it to the public in a way that’s user-friendly and easily accessible,” said Dowd-Uribe, associate professor in the international studies department at the University of San Francisco. “Whether or not GM crops can make a contribution to improved food security and poverty alleviation in Africa is of vital importance. We hope that our website can make a meaningful contribution towards improving the knowledge of these crops and projects, while advancing civic engagement around these issues.”

In all, the data catalogs 23 distinct crops – including cotton, wheat, rice, and sugarcane – with genetically modified variants under development, across 14 African countries. Thirty-two different crop varieties, 30 of which are either cotton or maize, have reached the commercialization stage. All commercialized crop varieties contain either pest resistance and/or herbicide tolerance traits.

But the mBio researchers found that only a small minority (14.8%) of these projects were driven by Africa-based institutions, while 82.8% of the crop varieties that reached commercialization were developed by for-profit institutions, despite funds originating from non-profit and government organizations.

“One of the big questions we asked is where GM crop development is taking place,” said Rock, assistant professor of development studies in the department of politics and international studies at University of Cambridge. “Our database shows that there has been a considerable amount of research within public institutions on the African continent, but that a majority of GM crops that become commercialized are developed mainly by non-African institutions. If African scientists and farmers are to be the groups who drive agricultural agendas, as many agree they should be, then this data offers an opportunity to reflect on how that goal can better be supported.”

A future update will include data from a corpus of nearly 2 million news articles published in Africa between 1997 and 2022 and research conducted by undergraduates in the UChicago Data Science Clinic and participants in the Data Science Institute Summer Lab. Students built a natural language processing pipeline analyzing the articles and revealing frequently-quoted experts and the sentiment of their comments on GM crops. In combination with the financial and scientific data, these results could be used to build a network of how the development and media coverage of GM crop research in Africa are entwined.

“This project couldn’t exist without data scientists who are interested in social engagement and social impact,” said Dowd-Uribe. “We couldn’t do this without the tools of data science; we could spend 10 years on our own as qualitative researchers trying to do something like this, but it might never come together. The marriage of social and data science was the key here.”