Professors Rebecca Willett and Ben Zhao Discuss the Future of AI on Public Radio

New artificial intelligence tools such as DALL-E and ChatGPT have made headlines recently for their uncanny ability to create realistic art and writing based on simple prompts. As the hype grows around these technologies and their impact upon society and the economy, many people wonder about their potential, challenges, and dangers.

On January 26th, Professors Rebecca Willett and Ben Zhao of the University of Chicago joined Wisconsin Public Radio to answer some of these questions from host Kate Archer Kent and listeners. The two discussed whether these models could replace human artists and writers, their possible value for health care and scientific research, the bias and ethics of AI, and security measures that might prevent their misuse.

Willett, Professor of Statistics and Computer Science and Faculty Director of AI at the Data Science Institute, commented on the complex economic and educational effects as artificial intelligence grows capable of performing what were previously considered exclusively human tasks.

Willett, Professor of Statistics and Computer Science and Faculty Director of AI at the Data Science Institute, commented on the complex economic and educational effects as artificial intelligence grows capable of performing what were previously considered exclusively human tasks.

“I think that there are some jobs that will not require as much human effort as they did previously. There is going to be a change to the economy,” Willet said. “But I think that we are going to see a need for new jobs, that there will be new roles that will emerge as we develop these various AI tools. So that is going to mean that we’ll have to rethink the way that we train students or workers, both at the university level and perhaps even the K through 12 level, but also as we think about training programs for mid-career professionals…There’s going to be a need for learning how to best work with and utilize these tools, how to use them ethically and responsibly and ensure that we’re not doing anything that hurts the underrepresented.”

Zhao, Neubauer Professor of Computer Science and a researcher on machine learning security, discussed the “cat and mouse” game of watermarking the output of AI models for imagery and text, as well as how society will need to think about the bias of these technologies as they are used for critical decision-making.

Zhao, Neubauer Professor of Computer Science and a researcher on machine learning security, discussed the “cat and mouse” game of watermarking the output of AI models for imagery and text, as well as how society will need to think about the bias of these technologies as they are used for critical decision-making.

“When you deal with other humans, you understand the existence of bias, you account for it in your mental calculus when you deal with them, and so it is easier to expect certain types of bias with certain people,” Zhao said. “For machine learning, one of the troublesome things about it is that it does have bias, there’s embedded bias inside that’s almost impossible to get rid of, only minimize. But at the same time, it is not obvious that it is there. So part of the issue with dealing with bias may be just getting people more aware that machine learning itself is, in many ways, like people. It has its own bias, because a lot of its training data comes from data generated by people. It is a product of society and culture and what we do, so it has that carried-in bias. And if we can understand that, that will help us deal with and accustomize ourselves to some of that bias and its impact.”

Listen to the full segment at Wisconsin Public Radio.

Community Data Fellow Stephania Tello Zamudio helps broaden internet access for Illinois residents

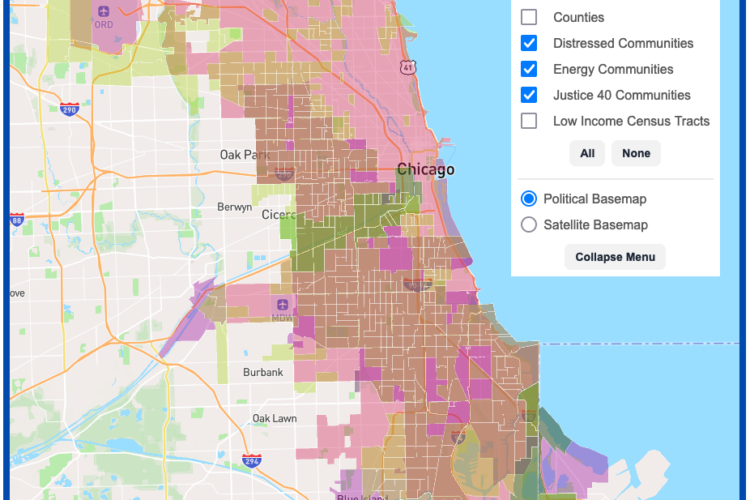

DSI Software Engineers create interactive map tool to maximize climate investment tax benefits

Transform cohort 3 participant Healee uses AI to improve healthcare