A Data-Driven Approach for Protein Design

Nature is an unparalleled engineer. Millions of years of evolution have created molecular machines capable of countless functions and survival in challenging ecological niches including deep sea vents and alkaline lakes. Scientists have long sought to harness these design skills and decode nature’s blueprints to build custom proteins of their own, for applications in medicine, energy production, environmental clean-up and more. But only recently have the computational and biochemical technologies needed to create that pipeline become possible.

At UChicago, researchers Andrew Ferguson and Rama Ranganathan are bringing these pieces together in an ambitious project funded by a CDAC Data Discovery seed grant. Combining recent advancements in machine learning, high-throughput gene synthesis, and rapid assays, they will build and prototype an iterative pipeline to learn nature’s rules for protein design, then remixing them to create synthetic proteins with elevated or even new functions and properties.

“It’s not just rebuilding what nature built, we can push it beyond what nature has ever shown us before,” added Ranganathan, the Joseph Regenstein Professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering, and the College. “The CDAC proposal is basically the starting point for building a whole framework of data-driven molecular engineering.”

Proteins are constructed from amino acids encoded by genes, and the explosion of genome sequencing over the last two decades has given scientists the blueprint for a broad range of proteins from thousands of species. But only recently have they started figuring out how these sequences encode higher-order rules for protein structure and function.

“The way we think of this project is we’re trying to mimic millions of years of evolution in the lab, using computation and experiments instead of natural selection.”

Andrew Ferguson, associate professor at the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering

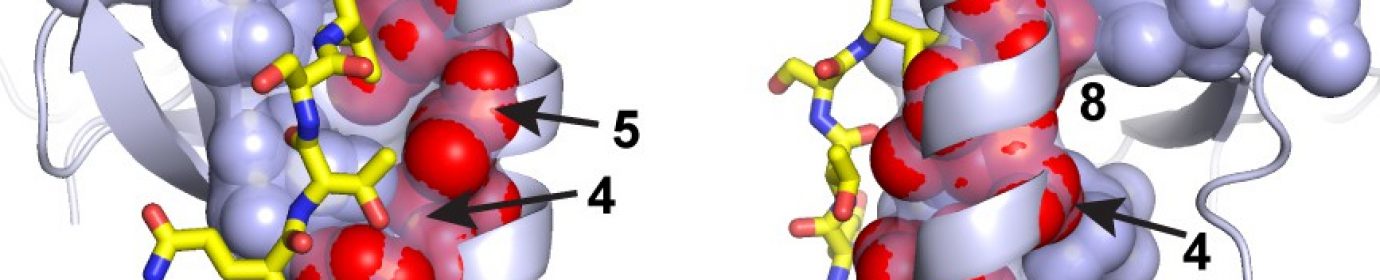

Machine learning promises to supercharge this pursuit, using the latest data mining techniques to infer these design rules from the diversity of known protein sequences. Ferguson, who has previously worked on machine learning models for designing vaccines, biomaterials, and organic electronics, will use a method called variational autoencoders (VAEs) in this project to reverse-engineer protein design. VAEs work similarly to how raw sound files are converted to mp3s, compressing data to a smaller size by only retaining the most important features.

But by looking at how a VAE reduces a large dataset to a small one, and the reverse process, computers and scientists can learn important information about the structure of the data and what it represents — in this case, a family of homologous proteins from various species.

“If you can train this model to do a good job at encoding and reconstructing its own input through this tight bottleneck, the bottleneck has told you that you have learned the essential features of the data that are necessary to reconstruct it,” said Ferguson, associate professor at the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering. “It essentially learns the design rules that nature came up with in the process of natural selection for these proteins.”

Once learned, those rules can then be manipulated to produce variations that have never been seen in nature. For example, the model could be told to modify an enzyme to work at extreme temperatures it would never encounter in the wild, or to execute its function on an entirely new substrate. The result would be a list of candidate genes, theoretically customized to specifications, but as yet untested — which is where Ranganathan’s laboratory comes in.

“You can design all the sequences you want in a computer, but those things live in a computer. You need them to live in the real physical world,” Ranganathan said.

With what they call “the gene machine,” Ranganathan’s group can rapidly synthesize the proteins suggested by the computer model. Then, using high-throughput experimental assays such as droplet microfluidics, they can test those synthetic proteins for their desired properties. Closing the loop, those results can then be fed back into the computer model, iteratively producing another round of candidates for further testing, until the functional goal is reached.

“The way we think of this project is we’re trying to mimic millions of years of evolution in the lab, using computation and experiments instead of natural selection,” Ferguson said.

Further down the road, the researchers believe this system could move beyond optimizing or changing the activity of proteins to designing molecular machines that can themselves evolve in new environments. Imagine an antibiotic that can adapt to bacterial resistance mutations, or an agent that cleans up polluted water and can modify itself to neutralize several different toxins.

“The idea that an existing machine can adapt itself, that is an interesting new concept,” Ranganathan said. “But it’s what evolution relies on, so if we really learn these rules, we should be able to build what I call complex, high-performance, adaptive matter. That is taking us into a space in which completely new engineering rules might be learned, beyond biology.”

Transform cohort 3 participant Healee uses AI to improve healthcare

Haifeng Xu named a AI2050 Early Career Fellow

Rebecca Willett awarded the SIAG DATA Career prize