Security, Online Speech, and A Better Web For All: Prof. Nick Feamster Joins CDAC and UChicago CS

It’s fair to describe the global internet as the skeleton of the modern world. As the internet has become ubiquitous, the staple computer science subdomain of networking has grown dramatically beyond its origins in electrical engineering, crossing over with other CS areas such as security and machine learning and branching out into policy and the social sciences. Today, hot-button issues such as state censorship and “fake news,” the privacy risks of smart devices, network neutrality, and equitable broadband access all come back to the science and technology of networking.

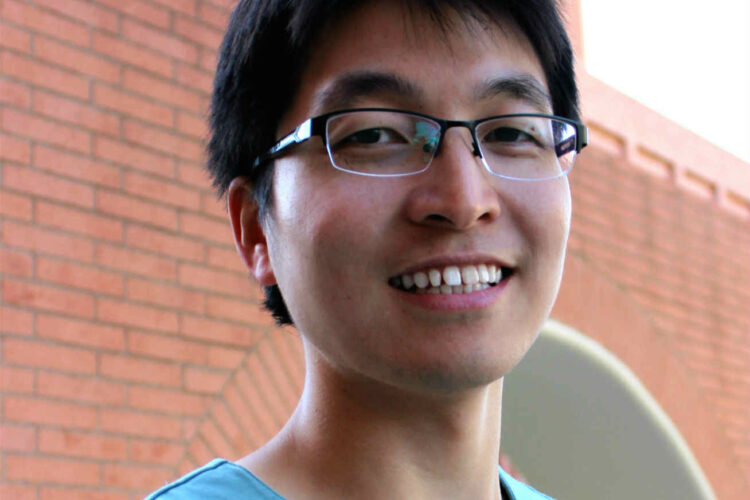

It’s this interdisciplinary perspective and broad impact that makes Nick Feamster passionate about networking, and that attracted him the University of Chicago, where he joined this summer as a Neubauer Professor of Computer Science and The College and faculty director of the Center for Data and Computing.

“Networking is a really interesting field because you can plug in at pretty much any layer,” Feamster said. “The pervasiveness of the technology, and the rapid pace of innovation excites me. You get to be a generalist in methods, but you also get to be a domain expert. It keeps you on your toes, you are constantly learning.”

Feamster’s track record is itself an archetype of how networking has grown and expanded in the last two decades. As a graduate student at MIT, his research laid the groundwork for the early phases of software-defined networking, the approach that underpins the traffic management of today’s internet. In 2010, he was named to the Technology Review list of top innovators under 35 for his work on spam detection, developing methods still in use by email providers today.

Recent research has led Feamster to explore new applications, including measuring how home internet speed affects streaming video quality for a Wall Street Journal investigation, determining how “smart” devices at home leak personal data, and developing methods for detecting state censorship of internet communication.

“My pattern in performing networking research, which has repeatedly been successful, is to figure out the right question to ask, and then build the system to get the data,” Feamster said. “Those steps turn out to produce really good computer science: you build a system that no one’s ever built it before, and you gather data that nobody else has, which ultimately allows you to answer questions that nobody else can answer as well as you can. That’s where things get really exciting.”

“As I thought about broadening the sphere of my own work into other interdisciplinary areas, the existence of other strong departments and excellent professional schools just seemed like it would open up a world of opportunities in the coming years. Ultimately, what we want to do is make a difference — to our communities, to students, to the institutions we work at — and ultimately to make the world a better place.”

Nick Feamster, Faculty Director of the Center for Data and Computing

From Spam to Misinformation and Censorship

Unwanted messages, or spam, are as old as the Internet itself. A cat-and-mouse game perpetually plays out between those tasked with filtering out these communications and those sending them. Traditionally, detection systems worked by scanning the text of the message for tell-tale signs of spam such as “offer” or “viagra,” but spammers got around those monitors through misspellings, hiding words in images, and other tricks.

While at Georgia Tech, Feamster pioneered a different approach, shifting the focus from the content of spam messages to the network-level signatures of spamming behavior. Because advertisers send out emails in bulk, their network traffic can be easily distinguished from that of a legitimate user, who typically sends messages at a far lower rate. By flagging suspicious network traffic, Feamster improved spam filtering, creating an approach still used to protect today’s inboxes.

What’s more, similar methods proved equally effective on subsequent trends in malicious internet activity, such as phishing and scam websites. Feamster’s group is now exploring whether the latest internet concern, online misinformation campaigns, can be fought by looking past the content to warning signs such as irregular website hosting and anomalous configuration of the web’s security protocols.

“The same problem that we were facing 10 or 15 years ago with spam has taken a new shape. The modern version of it is disinformation websites and social media — and, lo and behold, the same tricks for detecting unwanted messages work,” Feamster said.

A counterpoint to the spam research is Feamster’s work on circumventing internet censorship, where the game is not detecting messages, but eluding detection. One method he’s explored is hiding messages inside network traffic that looks innocuous from the outside, such as hiding a message organizing a protest in web traffic of Skype call.

“I’ve always been interested in efficient encoding of data, and that’s a very useful hammer when it comes to evading censorship,” Feamster said. “If you’re trying to sneak data through a censorship firewall, it’s all about taking information and encoding it so that it’s not recognizable.”

Speed and Privacy Inside The Home Network

Most of us connect to the global network via our home, where more and more devices communicate via the internet. Another major branch of Feamster’s research has focused on the issues that people encounter at this level, from download speeds to unnoticed privacy and security flaws. Feamster has developed systems for measuring home network activity to conduct empirical studies of home internet and trace problems back through the network to their technical — and sometimes political — origins.

“The broader vision is to make the network work for everybody,” Feamster said. “That means both consumers and also the people who run the networks. Better data and insights make the jobs of the operators easier, and consumers and policymakers also get better information; hopefully everyone’s better off as a result.”

Early work in this area required the creation of some of the first internet “speed tests,” so that researchers could compare the actual consumer experience to the data transfer rates promised by their service providers. More recently, Feamster’s group built technology to help the Wall Street Journal examine whether higher internet speeds affected the quality of home video streaming, concluding that pricier, faster plans only produced marginal benefits.

Another monitor of home internet activity inspired an unintentional research direction, as Feamster’s group started observing increasing traffic from devices other than computers, including security cameras, “smart” appliances, and even children’s toys. Digging deeper, they found that much of the data transferred by these technologies were unencrypted or otherwise non-secure, raising concerns about privacy.

That led Feamster to design a new tool, IoT Inspector, that informs users about what their devices are sending into the internet. At UChicago, he’ll work with colleagues such as Heather Zheng, Ben Zhao, and Pedro Lopes to form a new Internet of Things Privacy and Security group that will study how to protect consumers in this growing tech market.

Expanding the Interdisciplinary Network at UChicago

While he was studying the privacy risks of smart homes, Feamster began to see the potential for good beneath the worries about home devices snooping on their users. In the right hands, detailed information about an individual’s eating, sleeping, and activity could be used to help people make healthier lifestyle decisions, similar to wearable fitness trackers. To explore this possibility, he’s engaging the broad range of expertise at UChicago, already collaborating with experts from the University of Chicago Medicine.

“One of the things that excited me about UChicago and the interdisciplinary nature of the opportunities here was that there were a lot of people who were interested in those kinds of problems and wanted to talk to computer scientists,” Feamster said.

Feamster will also help facilitate more of these partnerships through his role as faculty director of the Center for Data and Computing (CDAC), the intellectual hub and incubator for data science and artificial intelligence research at UChicago. Through seed grants, research initiatives, and events, CDAC supports projects that cut across departments and schools on campus and address important scientific and societal questions with innovative computer science applications.

That mission matches Feamster’s own, both as a researcher and a teacher — this academic year, he’ll lead courses in online speech and internet censorship, and machine learning for public policy. With expertise in a field that can no longer operate in isolation given its importance to modern society, Feamster looks forward to developing his own network across campus.

“As I thought about broadening the sphere of my own work into other interdisciplinary areas, the existence of other strong departments and excellent professional schools just seemed like it would open up a world of opportunities in the coming years,” Feamster said. “Ultimately, what we want to do is make a difference — to our communities, to students, to the institutions we work at — and ultimately to make the world a better place.”

“UChicago is clearly a place where these values are deeply imbued in the culture,” he continued. “So many people here are engaged not only in their own research, but also in the community, the city, and society at large. The ethos is contagious. I could feel the buzz from the minute I stepped on the campus. The computer science department is also well in tune with the future of the discipline, and it has the resources that will allow us to be leaders in shaping the future of the field. Ultimately, I couldn’t resist getting hopping on the juggernaut; it’s the opportunity of a lifetime.”

Community Data Fellow Stephania Tello Zamudio helps broaden internet access for Illinois residents

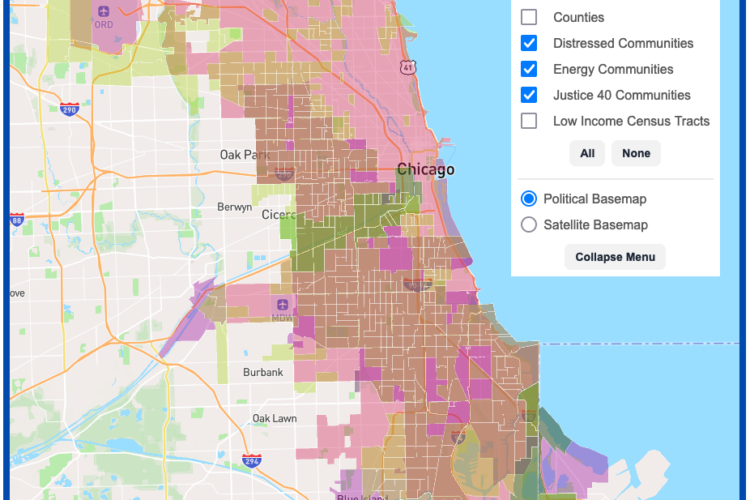

DSI Software Engineers create interactive map tool to maximize climate investment tax benefits

Transform cohort 3 participant Healee uses AI to improve healthcare