Improving Computer Perception…With Style

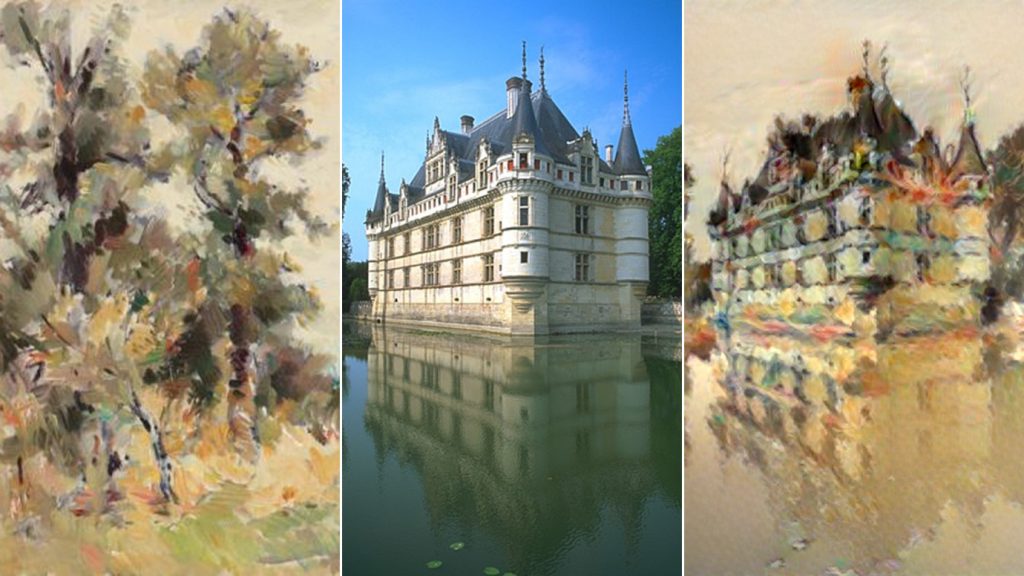

In recent years, several popular apps have gone viral promising to transform photographs into different artistic forms, from generic modes such as charcoal sketches or watercolors to the specific styles of Dali, Monet, and other masters. These “style transfer” apps use tools from the cutting edge of computer vision — primarily the neural networks that proven adept at image classification for applications such as image search and facial recognition.

But beyond the novelty of turning your selfie into a Picasso, these tools kick-start a deeper conversation around the nature of human perception. From a young age, humans are capable of separating the content of an image from its style, recognizing that photos of an actual bear, a stuffed teddy bear, or a bear made out of Legos all depict the same animal. What’s simple for humans can stump today’s computer vision systems, but Jason Salavon and Greg Shakhnarovich think the “magic trick” of style transfer could help them catch up.

“The fact that we can look at pictures that artists create and still understand what’s in them, even though they sometimes look very different from reality, seems to be closely related to the holy grail of machine perception: what makes the content of the image understandable to people,” said Greg Shakhnarovich, an associate professor at the Toyota Technological Institute of Chicago (TTIC).

In a project seeded through a CDAC Data Science Discovery grant, Salavon and Shakhnarovich will collaborate on new style transfer approaches that separate, capture, and manipulate content and style, unlocking new potential for art and science.

“We’re in a global arms race for making cool things happen with these technologies. From what would be called practical space to cultural space, there’s a lot of action,” said Salavon, an associate professor in the Department of Visual Arts at the University of Chicago and computational artist. “But ultimately, the idea is to get to some computational understanding of the ‘essence’ of images. That’s the rich philosophical question.”

At a high level, current style transfer techniques — including one method presented in a paper by Salavon, Shakhnarovich, and TTIC student Nicholas Kolkin earlier this year — feed a target image and style into a neural network, where features of each are extracted and combined. But truly representing both content and style must go deeper than merely substituting the details of photographs with the signature brushstrokes of Van Gogh or the color palette of Mondrian.

“The University is committed to cross-disciplinary enterprise, and this project fits right in. I really value that I’m able to form relationships with people in other fields and have productive, non-superficial kinds of interactions on things that seem so vital and interesting.”

Jason Salavon, associate professor of visual arts, University of Chicago

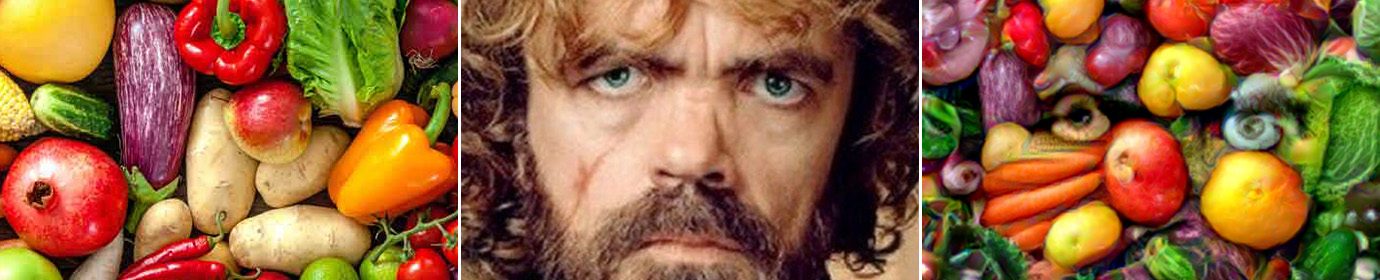

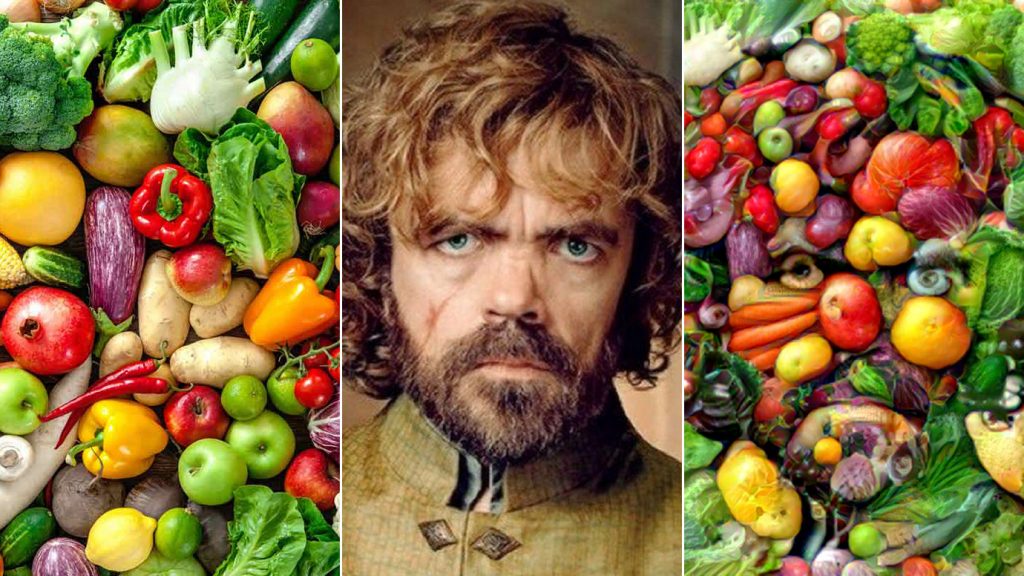

That’s because many artistic styles employ morphological transformation in depicting scenes or people. Think The Simpsons, where celebrities are rendered in the distinct caricature style of the show, but remain easy to recognize. What seems cartoony is actually a very nuanced blend of content and style, Salavon said.

“You cannot just make someone yellow and flat and have anybody believe it’s in the style of The Simpsons,” Salavon said. “You actually have to start deforming things and flattening simultaneously.”

As Salavon and Shakhnarovich continue to improve their style transfer model, they hope to add this capability for morphological changes, producing more extreme fusions of content and style. They’re drawing inspiration from pareidolia, the human tendency to see faces in inanimate objects such as clouds or rock formations, and the paintings of Giuseppe Arcimboldo, who portrayed his subjects as arrangements of fruits, vegetables, and other objects.

A computer model that can successfully create such hybrid images may get closer to reflecting important core features of human perception.

“In these images, we somehow simultaneously see both things at once,” Shakhnarovich said. “If you are interested in understanding perception, it seems very important to understand how we can see both a face and the fruit in an Arcimboldo. If we can create those things, then maybe it’s one measure of having understood, because being able to create something is the best way to check that you understand it.”

Those new perceptual abilities could help improve applications of computer vision, where rapid and accurate extraction of an image’s meaning in different contexts is critical for self-navigation, medical diagnostics, and other technologies. The model also creates new artistic opportunities that Salavon is already exploring in his studio (stay tuned). But uniting these scientific and artistic pursuits is a theoretical search for the fundamentals of human perception, expressed through the mathematical equations of machine learning.

“The University is committed to cross-disciplinary enterprise, and this project fits right in,” Salavon said. “I really value that I’m able to form relationships with people in other fields and have productive, non-superficial kinds of interactions on things that seem so vital and interesting.”

DSI Software Engineers create interactive map tool to maximize climate investment tax benefits

Transform cohort 3 participant Healee uses AI to improve healthcare

Haifeng Xu named a AI2050 Early Career Fellow