Searching for simplicity in microbial communities

Global nutrient cycles both provide the basis for the food webs that support life on Earth and control the levels of greenhouse gasses such as carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide in Earth’s atmosphere. Underlying these cycles are chemical transformations, for instance from organic carbon to carbon dioxide and nitrate to nitrogen gas, that are driven by the metabolic activity of microbial organisms.

My collaborators and I seek to understand the collective behavior of communities of these microbes. A key barrier to such an understanding is the complexity of these biological systems: for instance, each gram of soil can contain thousands of microbial strains. Each of these strains can, in principle, impact the activity of the other strains in the microbial community (microbial interactions) as well as contribute to the collective behavior of the community as whole (e.g., nutrient cycling). Additionally, microbial communities in the wild often reside in dynamic, spatially heterogeneous, and multi-dimensional environments. So how do we deal with this complexity?

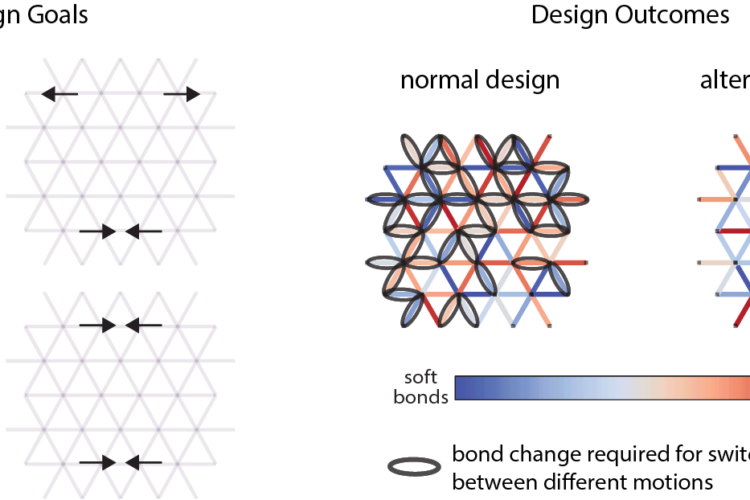

Motivated by the fields of statistical physics and systems biology, which find that systems that are complex at the microscopic level often give rise to simple collective behavior at the macroscopic level, we hypothesize that similar emergent simplicity is present in microbial communities. Indeed, recent theoretical and empirical studies have provided support for such a hypothesis, perhaps most influentially in a paper published in Science in 2018, which demonstrated a convergence in the composition of microbial communities extracted from 12 leaf and soil samples and assembled in controlled laboratory conditions. While this work undoubtedly represents a significant advance, it has garnered criticism from microbial ecologists, who point out that such experiments, which remove microbes from their natural habitats and impose a strong selection pressure for particular traits, are not a good representation of the experience of microbes in the wild. To avoid this complication, studies in microbial ecology often consist of genomic sequencing surveys, which sample microbial gene content from natural environments such as the ocean and topsoil, often associating variation in gene content with environmental factors. However, it is not possible to make causal statements about the role of the environment or microbial interactions in structuring microbial ecosystems from observational studies alone. As a result, there is a major gap between what we can learn from controlled laboratory studies and observations in the field.

To bridge this gap, we have developed an approach that provides a tantalizing glimpse of simplicity in natural microbial communities. Our approach seeks to connect laboratory experiments to patterns observed in field studies. To do this, we first identified a simple pattern that couples the abundance of two genes involved in the nitrogen cycle to pH in a global topsoil microbiome survey dataset: as pH increases, the relative abundance of one nitrate reductase gene (nap) increases, while the relative abundance of another nitrate reductase gene (nar) decreases. To understand the origin of this pattern, we needed the ability to perform laboratory experiments on the microbes involved. We therefore sampled soil from the environment, extracted microbial communities, and grew them in different pH conditions in the lab. Strikingly, we found that the same gene to pH coupling observed in the global survey data was reproduced in the lab across six soil samples! This allowed us to isolate and characterize the microbes that drive this pattern, revealing a pH-modulated interaction between microbes with the relevant genes. Crucially, this interaction seems to be conserved across microbial species, giving rise to the simple pattern identified in the survey data.

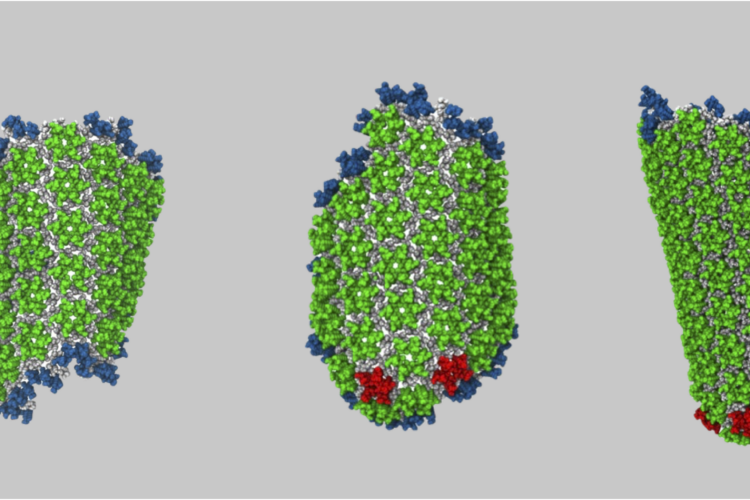

This finding raises an intriguing possibility: perhaps the activity of microbes is not species-dependent, but rather follows large-scale patterns that persist across many species. Is this phenomenon is a generic feature of natural microbial communities? To test this idea, we plan to subject intact soil samples to a suite of environmental perturbations and measure the response of both species abundances and community-level emission of carbon dioxide. Using machine learning tools such as variational autoencoders, we hope to identify a simplified description of the community that connects response patterns across species to carbon dioxide emission. Such a connection would help to elucidate the microbial basis for the global nutrient cycles that are essential for life on Earth.

Kyle is scheduled to join the Eric and Wendy Schmidt AI in Science Postdoctoral Fellowship, a program supported by Schmidt Sciences, in the Fall of 2024.