Teaching materials to adapt

Considered as materials, biological systems are striking in their ability to perform many individually demanding tasks in contexts that can often change over time. One noticeable feature of biological materials is their adaptability, the ability of a material to switch between mutually incompatible functions with minimal changes. Consider the skin of a chameleon; with just a few changes to the structure of pigments in its cells, a chameleon’s skin is capable of becoming a totally different color. What sort of processes could create materials which could also rapidly switch function, like a chameleon’s skin?

It turns out that the two key ingredients for producing adaptability in biology are fluctuating environments and having many designs which achieve the same function. By continually forcing organisms to adapt to different stresses, evolution in fluctuating environments selects for the rare design solutions which can be rapidly switched, should the environment fluctuate again.

My collaborators and I have been thinking about how this intuition can be adapted not just for biological systems which evolve, but also for materials which we design. We designed an elastic network to exhibit an out-of-phase allosteric motion – that is, if you pinch the network on the bottom, it will spread apart on the top. We also made networks that have in-phase allosteric motion – pinching these networks on the bottom will result in the network also pinching in on the top. For both of these motions, there are many different network designs which will achieve the desired motion. However, if you compare two random networks, one for each motion, you will see that the networks chosen are very different. Such networks are not adaptable; it would take many changes to the network structure in order to switch from one network to the other.

Excitingly, we found that if you alternate back and forth between designing first for the out-of-phase motion and then for the in-phase motion, the elastic network solutions you find will look very similar to each other! Therefore, despite the fact that the out-of-phase motion and the in-phase motion are totally opposite types of motions, we found materials which can rapidly adapt between them. Furthermore, just as our intuition from biology suggests, these adaptable networks are much rarer, and hence we needed the alternating design process to find them.

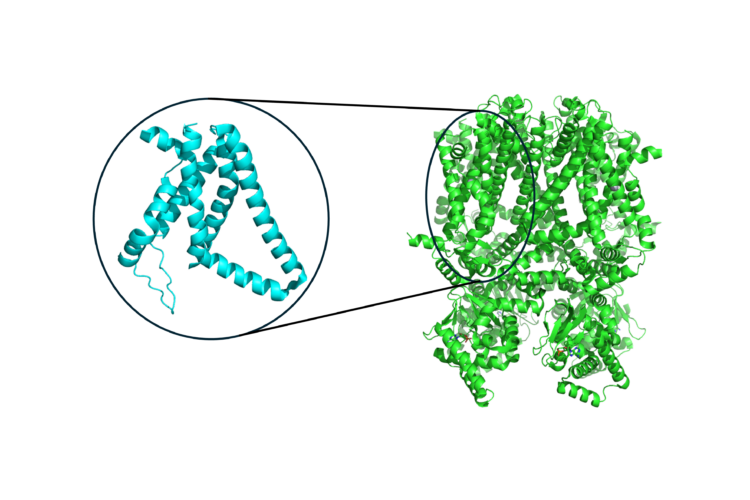

We also tested our alternating design process in two other kinds of material systems: elastic networks created to have different bulk material properties, as opposed to motions, as well as polymers created to fold into different structures, like proteins. In each case, we found that alternating design goals resulted in adaptable materials. In the case of the polymers folding into different structures, we were also able to identify a physical principle underlying the existence of these adaptable materials – the physics of phase transitions, the same physics underlying the tempering of chocolate. Therefore, our method not only worked, but also helped us to better understand how materials can be made to adapt.

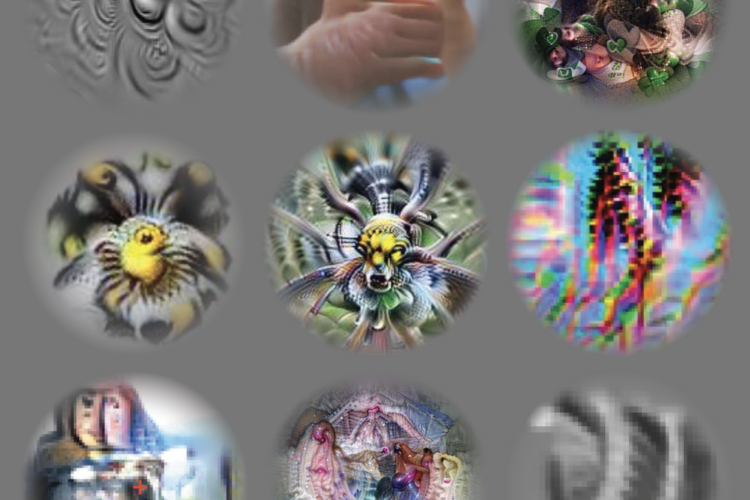

We’re excited by our alternating design procedure because it can be applied across a wide range of different materials, taking advantage of the unique aspects of each material in order to produce adaptability. In the future, we want to think about the implications of alternating design in artificial neural networks. Like our materials, artificial neural networks succeed because there are many different network configurations capable of fitting the data that the networks are trained on. However, neural networks are usually trained to perform a single (albeit complicated) task. Can we use inspiration from how nature adapts and changes to train artificial neural networks to have even more sophisticated properties?

This work was funded by the Eric and Wendy Schmidt AI in Science Postdoctoral Fellowship, a Program of Schmidt Futures.

Expanding Our Vocabulary of Vision Using AI

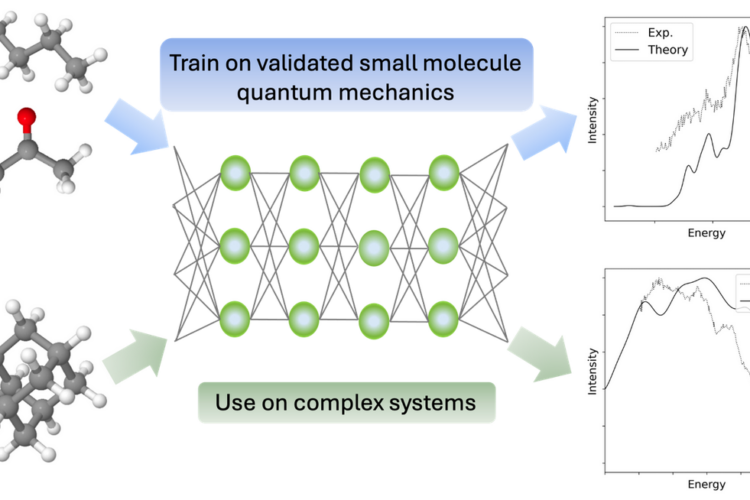

From Protein Structures to Clean Energy Materials to Cancer Therapies: Using AI to Understand and Exploit X-ray Damage Effects

Towards New Physics at Future Colliders: Machine Learning Optimized Detector and Accelerator Design