An Automated Menu for LHC Data and the Search for Dark Matter

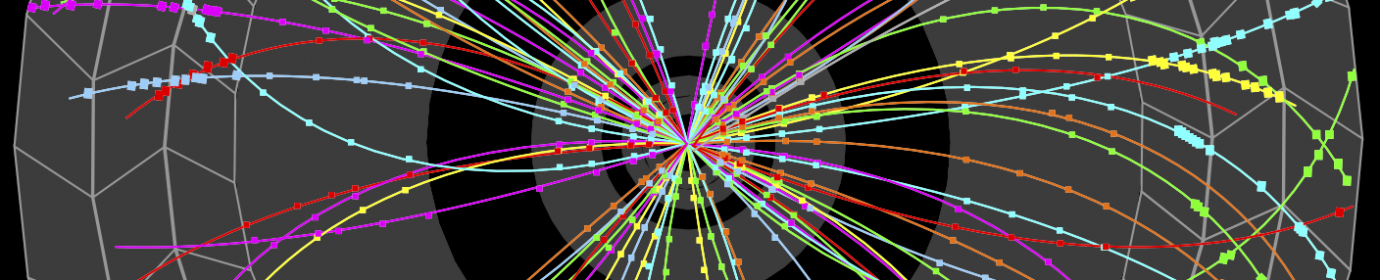

The Large Hadron Collider delivers an enormous smorgasbord of data. Normal operation of the particle collider at Europe’s CERN laboratory can generate up to 100 terabytes per second of heterogeneous, high-dimensional data. Because it wouldn’t be possible for scientists and their computers to store — never mind analyze — this firehose of physics results, they rely upon filters, or “trigger systems,” that only keep data containing what they think will be the most interesting scientific information.

Different versions of these trigger algorithms have been used in particle physics experiments for decades. But as the amount of data they filter grows faster than the storage and analysis capabilities of computers, new approaches are needed. Funded by a CDAC Discovery Grant, a new collaboration between physicist David Miller and computer scientist Yuxin Chen seeks to build upon advances in explainable AI and active learning to create a new, autonomously-driven trigger system that can aid one of today’s foremost scientific quests: the search for dark matter.

“This started from the ridiculous idea that you could have, instead of a self-driving car, a self-driving trigger, or event selection and filter system,” said Miller, Assistant Professor of Physics, The College, and the Enrico Fermi Institute. “Today, we throw away 99.99 percent of the data. So we asked, can we learn from what we’re throwing away? Can we learn how to do things better, and therefore, can the system that is doing the filtering learn over time what to keep and what to throw away, and whether it should update its own algorithm?”

Currently, the LHC operates with a “menu” of triggers that filter data according to rules set by physicists, drawing upon past results, theory, and informed guesses about where important results will be found in experiments. While these triggers perform well when physicists have a clear sense of what they’re looking for, they may be less capable of finding previously unobserved phenomena, such as dark matter. However, an algorithmic observer could alleviate these blindspots by making novel decisions on what data to keep, based on both previous decisions and its own, independent observations of the data as it goes zooming past.

But putting such a valuable task in the “hands” of an AI decision-maker is controversial to many in the physics world, Miller said.

“Nobody’s even written a concept paper of what this ridiculous idea even means,” Miller said. “None of my physics colleagues would go for it, at least at the moment, because no one wants to let some black box make your decisions for you.”

But a recent move in the machine learning world towards “white box” or “explainable AI” could help bridge this confidence gap. Here, an algorithm wouldn’t just recommend that a certain type of data should be kept, it would also explain how it arrived at that decision. To further reassure physicists, Miller and Chen’s project will start by attempting to recreate the current, human-crafted triggers with their new approach, training the model on both real and simulated data and observing whether it keeps the same results as the current filters.

When it comes to creating new filters that haven’t already been proposed by its human counterparts, the model will draw upon another two promising threads of AI research: online learning and active learning. Instead of earlier machine learning models, which are trained once on a large dataset and then make decisions or predictions on new data, an online learning model constantly evolves, updating its decision rules as each new data point comes in.

Meanwhile, active learning allows the model to autonomously decide which data points are the most promising to keep to help make future decisions. These characteristics make such techniques well suited for streaming data, such as the constant flow of information from financial markets or security cameras, but also from the LHC — the largest stream of all.

The fact that LHC data pours in so fast and in such volume will test the limits of state-of-the-art stream-based active learning approaches, and likely lead to new innovations that can benefit other applications.

“There are a lot of connections with other areas such as high frequency trading, where systems have to scan through all this financial data and make real time decisions, or video processing, making efficient summarization of useful traits of scenes with limited processing power,” Chen said. “So hopefully the techniques we develop for this project will be applicable for a lot of other domains.”

The project also may intersect with other CDAC projects involving Miller and Chen, including a Winter 2019 CDAC Discovery grant to build neural networks for analysis that draw upon the physical laws governing subatomic particles, and an AI + Science grant that seeks to build a “self-driving telescope” for cosmic surveys. Combined, these research efforts show the exciting potential of AI for the large-scale physics projects that help us better understand our universe.

“[These projects] are where this interplay of the physical sciences and the computer sciences is really interesting,” Miller said. “We’re after answers to fundamental questions about what particles exist in the universe, under what conditions they are produced, and how they behave once we’ve created them. To be able to apply this new approach in a context where we have practically an unlimited amount of data, and where we plan on taking a lot more new data in the near and distant future, is really intriguing.”

Community Data Fellow Stephania Tello Zamudio helps broaden internet access for Illinois residents

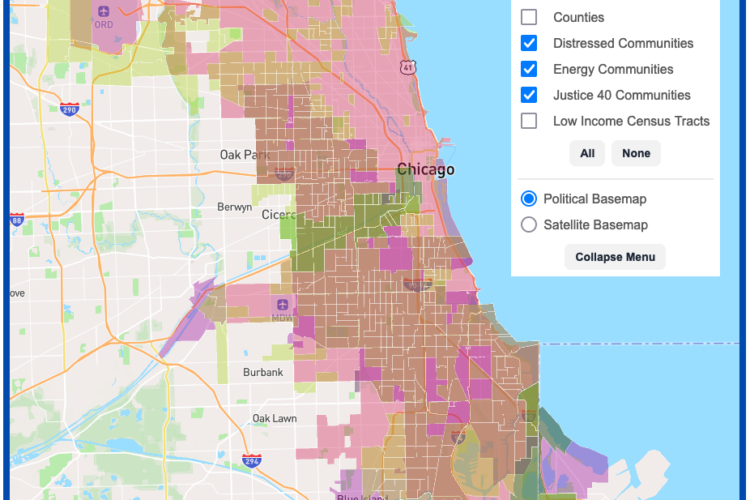

DSI Software Engineers create interactive map tool to maximize climate investment tax benefits

Transform cohort 3 participant Healee uses AI to improve healthcare