Uncovering Patterns in Structure for Voltage Sensing Membrane Proteins with Machine Learning

How do organisms react to external stimuli? The molecular details of this puzzle remain unsolved.

Humans, in particular, are multi-scale organisms. Various biological systems (i.e. the respiratory system, digestive system, cardiovascular system, endocrine system, etc.) comprise the human body. Within each of these systems, there are organs, which are made of tissues. Each tissue is then made of cells. Within cells, there are smaller pieces of machinery known as organelles. Cells and organelles are composed of a variety of proteins and lipids. In particular, proteins that are embedded in lipids (as opposed to floating within the cell) are known as membrane proteins.

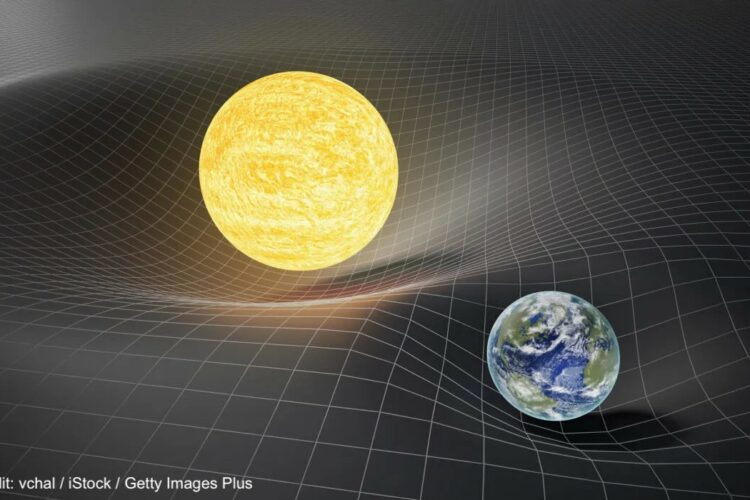

Although there are clear differences between organisms (i.e. bacteria, humans, and mice) at the cellular and atomic scales, the protein machinery looks very similar. Indeed, challenges in predicting protein structure led to the breakthrough of AlphaFold, enabling scientists to make predictions on protein structure given a primary sequence of amino acids (the building blocks of proteins). Cells and organelles across different organisms sense stimuli such as touch, heat, and voltage with a specific type of protein called a membrane protein. These membrane proteins are usually embedded on the membrane that defines the “inside” and “outside” of a cell or an organelle, and thus are responsible for sensing. Despite advances in protein structure prediction with AlphaFold, challenges remain for predicting the structures of membrane proteins. We can utilize existing experimental structures, however, to try and decipher patterns for voltage sensing.

Voltage Sensing Proteins

Voltage sensing membrane proteins are specialized molecular entities found in the cell membranes of various organisms, ranging from bacteria to humans. These remarkable proteins play a pivotal role in cellular function by detecting and responding to changes in the electrical potential across the cell membrane. Through their sophisticated structure and mechanisms, voltage sensing membrane proteins enable cells to perceive, process, and transmit electrical signals essential for vital physiological processes such as neuronal communication (i.e. passing action potentials), muscle contraction, and cardiac rhythm regulation. For instance, neurons have voltage-gated ion channels – channels that open and allow the flux of ions into the cell to produce electrical signals.

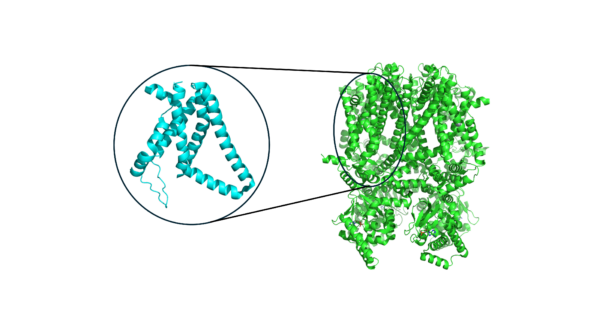

Despite the complexity of voltage sensing proteins that are able to sense different voltages with high sensitivity, the biology of voltage sensors is highly modular. Proteins that respond to voltage typically have what is known as a “voltage sensing domain,” or VSD. The VSD is usually coupled to a larger module that is responsible for function. For instance, in a voltage-gated ion channel, the ion channel itself is coupled to one or more VSDs that enable it to behave in a voltage-sensitive way. The modular nature of the VSD, which is nearly always a 4-helix bundle, enables comparison across VSDs from different proteins (and organisms!) using machine learning. Over the full protein data bank (PDB) where protein structures are deposited by experimental structural biologists, we can extract thousands of VSDs from various proteins.

Analogy to Modified NIST (MNIST) Digit Dataset

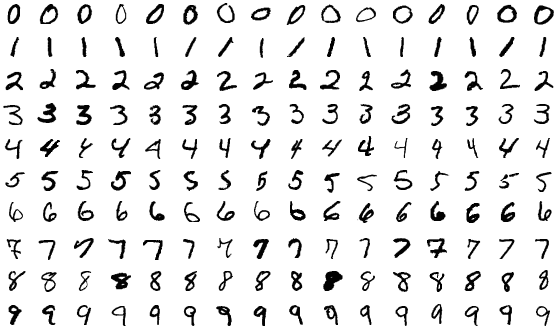

At its root, we would like to determine any patterns between voltage sensors that may have similar function, turning the problem into one of “pattern recognition” that can be tackled with machine learning. Analogous pattern recognition problems have been carried out by computer scientists for decades. The MNIST data set is a classic task in machine learning for classifying hand-written digits. The key concept in classifying MNIST digits is that each digit has a set of characteristics, or “features,” that underlies its membership to a certain label (in this case, 1 through 9). Humans can identify these digits, but a machine learning model must pick out the key similarities and differences between these digits to separate them.

In a similar vein, VSDs must have underlying features and characteristics that make them uniquely sensitive to different voltages. One key difference that makes working with scientific data more challenging than MNIST is that we do not always have labels. Or more specifically, we do not know the sensitivity of the voltage sensor unless a functional study has been carried out.

The Excitement

Using machine learning to fingerprint and cluster VSDs represents an opportunity to move beyond sequence-to-structure prediction, like AlphaFold, and on to structure-to-function analysis. Through analyses on structural similarities and differences, we may be able to discern the molecular basis for voltage sensitivity and the key structural features that are essential for a protein to respond to voltage. Understanding this response to voltage can help us understand how the molecular machinery of the body behaves under native and diseased conditions.

Together with the Vaikuntanathan, Roux, and Perozo laboratories and the newly formed Center for Mechanical Excitability at the University of Chicago, I continue to investigate voltage-sensitive proteins to understand how they underlie how cells respond to stimuli.

This work was funded by the Eric and Wendy Schmidt AI in Science Postdoctoral Fellowship, a Program of Schmidt Futures.

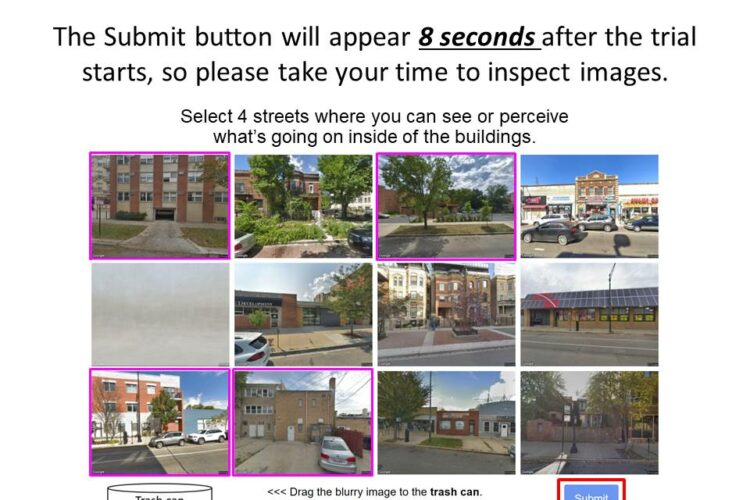

Using Computer Vision to Study Chicago Neighborhoods

Towards New Physics at Future Colliders: Machine Learning Optimized Detector and Accelerator Design

Finding the likely causes when potential explanatory factors look alike