Towards New Physics at Future Colliders: Machine Learning Optimized Detector and Accelerator Design

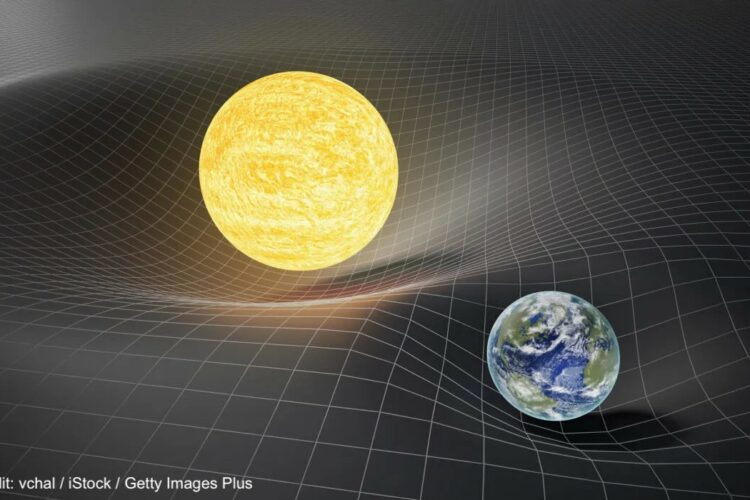

We are in an exciting and challenging era of fundamental physics. Following the discovery of the Higgs boson at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC), there have been 10 years of searches for new physics without discovery. The LHC, shown below, collides protons at nearly the speed of light to convert large quantities of energy to exotic forms of matter via the energy-mass relationship E=mc2. The goal of our searches is to discover new particles which could answer some of the universe’s most fundamental questions. What role does the Higgs play in the origin and evolution of the Universe? What is the nature of dark matter? Why is there more matter than antimatter in the universe? Given the absence of new particles, the field is devising new methods, technologies, and theories. Some of the most exciting work is towards building more powerful colliders. In this work, an emerging theme is the use of machine learning (ML) to guide detector and accelerator designs.

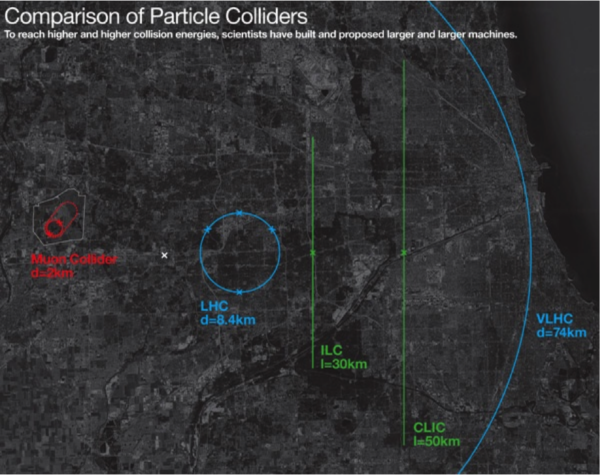

The goal of building new colliders is to precisely measure known parameters and attempt to directly produce new particles. As of 2024, the most promising designs for future colliders are the Future Circular Collider (FCC), Circular Electron Positron Collider (CEPC), International Linear Collider (ILC), and Muon Collider (MuC). The main difference between the proposals is the type of colliding particles (electrons/positrons, muons/anti-muons, protons-protons), the shape (circular/linear), the collision energy (hundreds vs. thousands of gigaelectronvolts), and the collider size (10 – 100 km). A comparison between the current LHC and proposed future colliders is shown below.

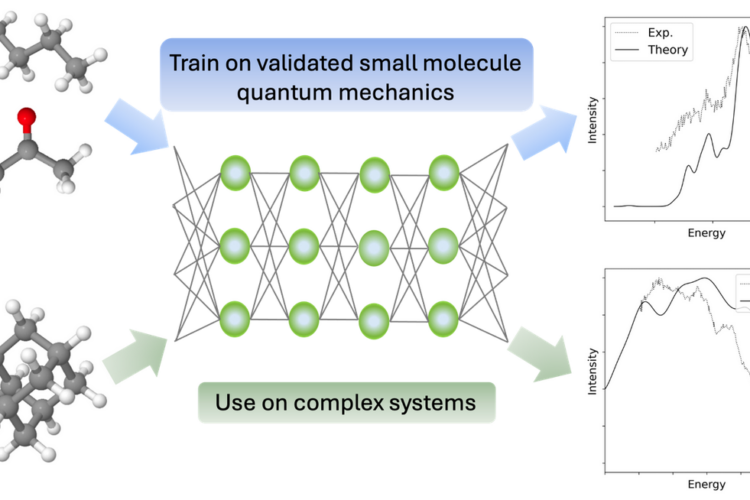

Designing the accelerator and detector complexes for future colliders is a challenging task. The design involves detailed simulations of theoretical models and particle interactions with matter. Often, these simulations are computationally expensive, which constrains the possible design space. There is ongoing work to overcome this computational challenge by applying advances in surrogate modeling and Bayesian optimization. Surrogate modeling is the technique for creating a fast approximate simulation of an expensive, slow simulation, increasingly using neural networks. Bayesian optimization is a technique to optimize black box functions without assuming any functional forms. The combination of these approaches can reduce computing expenses considerably.

An example of ML guided optimization is ongoing for one of the outstanding challenges for a MuC. A MuC is an exciting future collider proposal that would be able to reach high energies in a significantly smaller circumference ring than other options. To create this machine, we must produce, accelerate, and collide muons before they decay. A muon is a particle similar to the electron but around 200 times heavier. The most promising avenue for this monumental challenge starts by hitting a powerful proton beam on a fixed target to produce pions, which then decay into muons. The resulting cloud of muons is roughly the size of a basketball and needs to be cooled into a 25µm size beam within a few microseconds. Once cooled, the beam can be rapidly accelerated and brought to collide. The ability to produce compact muon beams is the missing technology for a muon collider. Previously proposed cooling methods did not meet physics needs and relied on ultra-powerful magnets beyond existing technology. There are alternative designs that could remedy the need for powerful magnets, but optimization of the designs is a significant hurdle to assessing their viability.

In a growing partnership between Fermilab and UChicago, we are studying how to optimize a muon-cooling device with hundreds of intertwined parameters. Each optimization step will require evaluating time and resource intensive simulations, constraining design possibilities. So, we are attempting to build surrogates of the cooling simulations and apply Bayesian optimization on the full design landscape. There have been preliminary results by researchers in Europe that show this approach has potential, but more work is needed.

To make progress on this problem, we are starting simple – trying to reproduce previous results from classical optimization methods. Led by UChicago undergraduates Daniel Fu and Ryan Michaud, we are performing bayesian optimization using gaussian processes. This does not include any neural networks but helps build our intuition for the optimization landscape and mechanics of the problem. The first step of this process is determining if the expensive simulation can be approximated by a gaussian process to produce a fast surrogate. If it can be then the optimization can proceed. If not then we’ll need to deploy a more complex model like a neural network. We hope to have preliminary results by the summer ‘24 and contribute to the upcoming European strategy update for particle physics.

This work was funded by the Eric and Wendy Schmidt AI in Science Postdoctoral Fellowship, a Program of Schmidt Futures.

From Protein Structures to Clean Energy Materials to Cancer Therapies: Using AI to Understand and Exploit X-ray Damage Effects

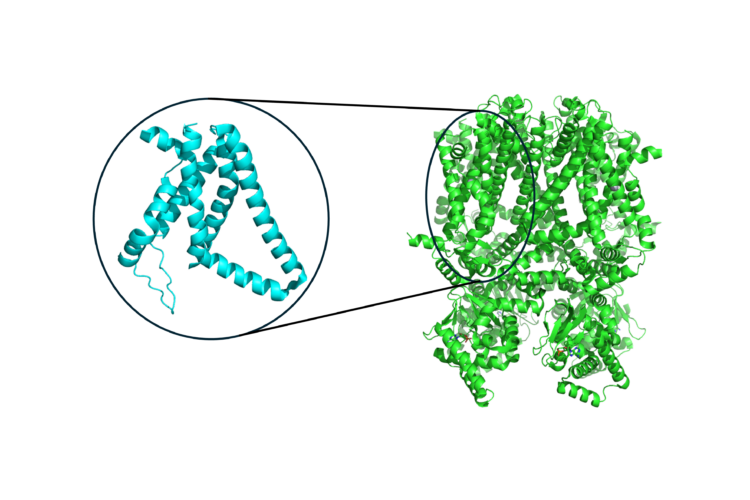

Uncovering Patterns in Structure for Voltage Sensing Membrane Proteins with Machine Learning

Finding the likely causes when potential explanatory factors look alike