An Intro to Gravitational-Wave Astronomy

For all of human history, astronomy has consisted of the study of light. Different wavelengths of light are detected in different ways and used for different purposes. Traditional telescopes collect and focus optical light (the same wavelengths seen by the eye) in order to view distant stars and galaxies. Large radio dishes capture the much lower frequency radio waves that comprise the Cosmic Microwave Background, a baby picture of the early Universe. And x-ray telescopes in orbit around the Earth catch bursts of high-energy light from all manner of explosions throughout the Universe. Whatever the wavelength, though, these are all differential realizations of the same physical phenomenon: ripples in the electromagnetic field, a.k.a. electromagnetic waves, a.k.a. light.

Humanity’s astronomical toolkit categorically expanded in September 2015, with the first detection of a new kind of astronomical phenomenon: a gravitational wave. Gravitational waves are exactly what they sound like: a ripple in gravity. The new ability to detect and study these gravitational waves offers an entirely new means of studying the Universe around us, one that has allowed us to study never before seen objects in uncharted regions of the cosmos. I am one of two Eric and Wendy Schmidt AI in Science Postdoctoral Fellows (along with Colm Talbot) who study gravitational waves. I therefore want to broadly introduce this topic — what gravitational waves are and how they are detected — in order to set the stage for future posts exploring gravitational-wave data analysis and the opportunities afforded by machine learning.

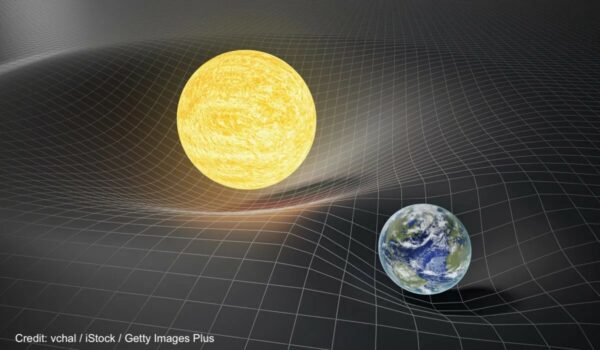

If you have spent any time watching the History Channel or reading popular science articles, you have probably encountered the idea of gravity as curvature. Today, physicists understand the nature of gravity via Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity, which describes gravity not as an active force that grabs and pulls objects, but as the passive curvature or warping of space and time (together known as spacetime) by matter. The Earth, for example, is not kept in its orbit via a force exerted by the Sun. Instead, the Sun curves the surrounding fabric of spacetime, and the Earth’s motion along this curved surface inscribes a circle, just like a marble rolling on some curved tabletop. This arrangement is often summarized as follows: “Matter tells spacetime how to bend, spacetime tells matter how to move.”

With this analogy in mind, now imagine doing something really catastrophic: crash two stars together; let the Sun explode; initiate the birth of a new Universe in a Big Bang. Intuition suggests that the fabric of spacetime would not go undisturbed by these events, but would bend and vibrate and twist in response. This intuition is correct. These kinds of events indeed generate waves in spacetime, and are what we call gravitational waves. Strictly speaking, almost any matter in motion can generate gravitational waves. The Earth generates gravitational waves as it orbits the Sun. You generate gravitational waves any time you move. In practice, however, only the most violent and extreme events in the Universe produce gravitational waves that are remotely noticeable, and even these end up being extraordinarily weak. To explain what exactly I mean “extraordinarily weak,” I first have to tell you what gravitational waves do.

I introduced gravitational waves via an analogy to light; the latter is a ripple in the electromagnetic field and the former a ripple in the gravitational field. This description, though hopefully intuitive, masks a fundamental peculiarity of gravitational waves. All other waves — light, sound waves, water waves, etc. — are phenomena that necessarily move inside of space and time (it would not make sense for anything to exist outside space and time!). Gravitational waves, though, are ripples of space and time. There is no static frame of reference with which to view gravitational waves; gravitational waves manifest as perturbations to the frame itself.

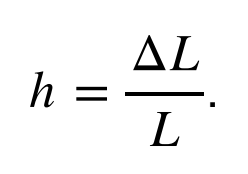

What does this mean in practice? The physical effect of a gravitational wave is to modulate the distances between objects. Imagine two astronauts floating freely in space. A passing gravitational wave will stretch and shrink the distance between them. Critically, this occurs not because the astronauts move (they remain motionless), but because the space itself between them literally grows and shrinks (think of Doctor Who’s Tardis, wizarding world tents in Harry Potter, the House of Leaves’s House of Leaves). The strength of a gravitational wave, called the gravitational-wave strain and denoted h, describes this change in distance induced between two objects, ΔL, relative to their starting distance L:

This change in length is exactly how gravitational waves are detected. Gravitational waves are detected by a network of instruments across the globe, all of which use lasers to very precisely monitor the distances between mirrors separated by several kilometers. These mirrors are exquisitely isolated from the environment; to detect a gravitational wave, you must be utterly confident that the distances between your mirrors fluctuated due to a passing ripple in spacetime and not because of minuscule disturbances due to a car driving by, Earth’s seismic activity, ocean waves hitting the coast hundreds of miles away, etc.

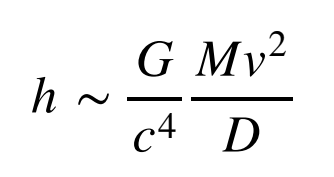

What kinds of events can we observe via gravitational waves, utilizing these detectors? Consider an object of mass M moving at speed v some distance D away. The gravitational wave strain you experience from this object is, to an order of magnitude,

Here, I’ve used two additional symbols. The quantity ![]() is Newton’s gravitational constant and

is Newton’s gravitational constant and ![]() is the speed of light. Note that G is a very small number and c a very large number, so the ratio

is the speed of light. Note that G is a very small number and c a very large number, so the ratio ![]() in the equation above is extremely small, working out to about

in the equation above is extremely small, working out to about ![]() ! The extraordinary smallness of this number means that gravitational waves produced by everyday objects are so infinitesimal as to be effectively non-existent. Consider someone waving their arms (with, say mass M ∼ 10 kg at speed

! The extraordinary smallness of this number means that gravitational waves produced by everyday objects are so infinitesimal as to be effectively non-existent. Consider someone waving their arms (with, say mass M ∼ 10 kg at speed ![]() ) at a distance of one meter away from you. Plugging these numbers in above, we find that you would experience a gravitational-wave strain of only h ∼ 10^−44.

) at a distance of one meter away from you. Plugging these numbers in above, we find that you would experience a gravitational-wave strain of only h ∼ 10^−44.

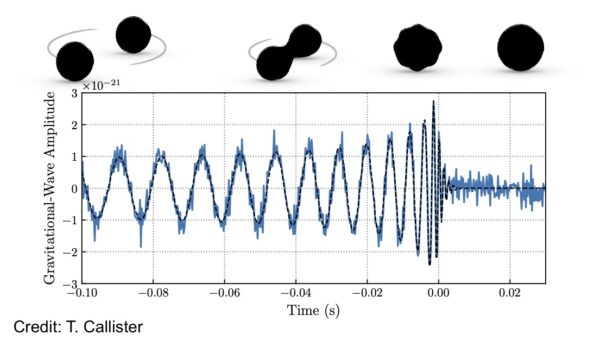

The important takeaway is that only the most massive and fastest-moving objects in the Universe will generate physically observable gravitational waves. One example of a massive and fast-moving system: a collision between two black holes. The Universe is filled with black holes, and sometimes pairs of these black holes succeed in finding each other and forming an orbiting binary. Over time, as these black holes emit gravitational waves, they lose energy and sink deeper and deeper in one another’s gravitational potential. As they sink closer together, the black holes move ever faster, in turn generating stronger gravitational-wave emission and hastening their progress in an accelerating feedback loop. Eventually, the black holes will slam together at very nearly the speed of light. This entire process is called a binary black hole merger. How strong are the final gravitational waves from these black hole mergers? Let’s plug some numbers into our equation above. Assume that the black holes are ten times the mass of our sun, M ∼ 2 × 10^31 kg, that they are moving at the speed of light, v ∼ c, and that they are a Gigaparsec (i.e. a few billion light years) away, D ∼ 3 × 10^25 m. The resulting gravitational-wave strain at Earth is approximately h ∼ 10^−22.

A binary black hole merger is just about the most massive and fastest moving system the Universe can provide us. And yet the gravitational waves it generates are still astonishingly small. To successfully measure waves of this size, gravitational-wave detectors have to track changes of size ΔL ∼ 10^−19 m in the distances between their mirrors. This is a distance one billion times smaller than the size of an atom. It is equivalent to measuring the distance to the nearest star to less than the width of a human hair. And although this sounds like an impossible task (and indeed was believed to be so for almost a century), decades of technological and scientific advancements have made it a reality. In September 2015, the gravitational-wave signal from a merging binary black hole a billion light years away was detected by the Advanced LIGO experiment, initiating the field of observational gravitational-wave astronomy.

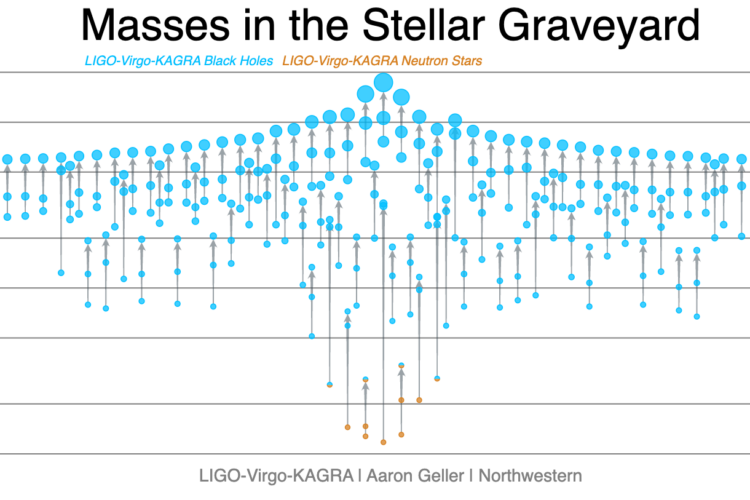

We now live in a world in which gravitational-wave detection is a regular phenomenon. To date, about 150 gravitational-wave events have been witnessed. Most of these are from black hole collisions, and a handful involve the collisions of another class of object called a neutron star. How do we know the identities of these gravitational wave sources? And how does this knowledge help us study the Universe around us? (And where does machine learning come in??). Stay tuned to find out!

This work was funded by the Eric and Wendy Schmidt AI in Science Postdoctoral Fellowship, a Program of Schmidt Futures.

Towards New Physics at Future Colliders: Machine Learning Optimized Detector and Accelerator Design

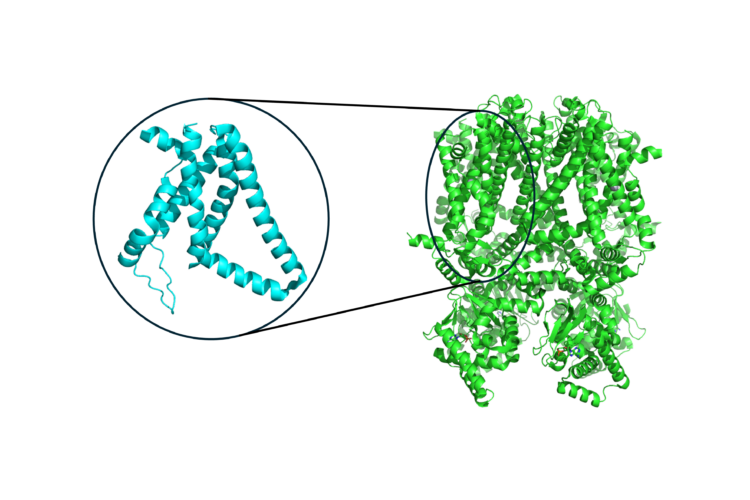

Uncovering Patterns in Structure for Voltage Sensing Membrane Proteins with Machine Learning

Finding the likely causes when potential explanatory factors look alike