Spatial Immunity: A new perspective enabled by computer vision

Our immune systems are complex and dynamic systems that help us survive when something goes wrong. Our bodies have developed little cellular armies that can take on all kinds of foes; they help to heal wounds, fight foreign invaders – like the common cold or COVID-19, and even battle cancer. There are many cell types that make up our immune systems, each having their own specialty. Some cells survey their native tissues, waiting for something insidious to come along. Other cells wait for the signal to build up their army – or proliferate – and mount an attack on that suspicious object. There are message-passing cells, killer cells, cells that act as weapon (or antibody) factories, cells that clean up the aftermath of an attack, and cells that keep the memory of the invader in case it’s ever seen again. A well-functioning immune system helps us to lead functional, long lives.

However, our immune systems are not always well-oiled machines. Autoimmune conditions are disorders where the immune system starts to attack normal, otherwise healthy tissue. These conditions can affect tissues and organs from any part of the body, ranging from rheumatoid arthritis, which affects the tissue in small joints; to multiple sclerosis, which affects the protective covering of nerves; to type 1 diabetes, which affects the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. These conditions can all make everyday activities difficult, and even become life-threatening. In general, scientists understand the immune cell “major players” in many of these conditions, but sometimes these findings don’t translate effectively to patient care.

In patients diagnosed with lupus nephritis (an autoimmune condition that affects the kidneys), only about 15-20% of patients that are treated with existing therapies will respond to those therapies. And not responding to those therapies can have dire consequences – either a lifetime on dialysis or getting on a waitlist to receive a life-saving kidney transplant.

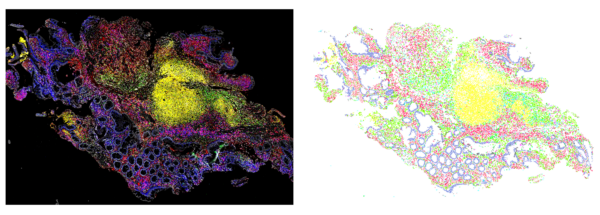

To effectively treat these conditions, we must first better understand them. New methods for imaging immune cells in their native tissue are helping us to uncover the differences between patients who do and do not respond to the current standard of care. Until recently, we have studied immune cells by taking them out of the affected tissue and testing them. Using these new imaging methods, we can now look at the diverse set of soldiers in these dysfunctional cellular armies while their “formations” are still intact. To do this, a small piece of tissue is taken from the affected organ and imaged with up to 60 different cell-tagging molecules. The resulting images are rich and complex – so much so that a human cannot easily interpret them. This is where artificial intelligence (AI), and more specifically computer vision, saves the day. We train a specific type of AI algorithm called a convolutional neural network (CNN) to find the tens of thousands of cells in the image of that small sample of tissue. We can then use other classification methods to go cell-by-cell to figure out if that cell is a ‘native tissue’ cell, like a blood vessel or another structural cell, or if that cell is an immune cell and importantly: what type of immune cell it is.

Once we have this detailed map of where all of the different tissue cells and immune cells are, we can look at differences between these maps in patients who did and did not respond to therapy. In lupus nephritis, we found that a high density of B cells (one specific type of immune cell) was associated with kidney survival – meaning those patients likely responded to therapy. Also, small groups of a specific subset of T cells (a different type of immune cell) meant that a patient’s disease would continue to progress, even when treated with the standard of care.

Studying spatial immunity – or the spatial distribution of immune cells – is only possible with the advent of new computer vision methods, or clever applications of existing ones. AI has not just revolutionized this work, but built the foundations for it. As we create better models for mapping immune cells and their spatial relationships, we’ll continue to learn more about what happens when our immune system malfunctions, and hopefully better prepare therapies for when it does.

This work was funded by the Eric and Wendy Schmidt AI in Science Postdoctoral Fellowship, a Program of Schmidt Futures.